Read the article on Vancouver Is Awesome

If you look over your back fence this week and your neighbours are building a fort in the rain and decorating it with tree boughs, fruits and vegetables, don’t worry. They’re not crazy. They’re probably Jews.

Autumn is a time when Jewish holy days, both joyous and deeply solemn, are packed together. This one — well, officially, it’s three holidays covering nine days that blend together — is festive, unlike the repentant and deeply reflective Yom Kippur, which closed the High Holy Days a mere six days ago.

The harvest festival of Sukkot began Wednesday at sundown and ends next Wednesday. The name “Sukkot” is simply the plural version of the temporary shelter — a “sukkah,” or “booth” — that observant Jews build in their back yards, and which have multiple symbolic meanings.

“For most of our history, Jews were an agricultural people, closely tied to the land,” says Rabbi Dan Moskovitz. “So even though most Jews outside of Israel are more urbanized, we still celebrate holidays that are related to the harvest and its bounties, because the harvest and nature are evidence of God’s miraculous presence and God’s blessing.”

Historically, the “booths” were where the ancient Israelites lived while reaping the harvest and, like probably all agricultural societies, a harvest festival ensued, explaining the party atmosphere in today’s makeshift shelters.

The sukkah is also said to symbolize the essential experience in the Jewish historical narrative: the escape from slavery in Egypt and the 40-year adventure of the Exodus while the Israelites made their way to freedom, became a nation and received the word of God at Sinai.

Above all, Moskovitz says, the sukkah is a reminder of the temporariness and fragility of everything, including life.

This is only Moskovitz’s second holiday cycle here, having moved to Vancouver after 13 years as a rabbi at a large Los Angles synagogue. He took the helm at Temple Sholom, a Reform synagogue on Oak Street, north of 70th Avenue, in 2013.

Last year, when the rabbi told his young kids they would sleep that night in the sukkah, as per tradition, resistance due to rain was deflected with some not-so-ancient Jewish wisdom.

“Home Depot sells tarps,” he says.

Like many, if not most, holy celebrations, Sukkot has a universal message — especially so this year as Sukkot overlaps with Thanksgiving.

“So often we take for granted the blessings in our life and Sukkot, the harvest holiday, reminds us of our connection to the earth and that all that we enjoy and appreciate doesn’t come only from us. It comes to us in partnership with nature and in partnership with God,” says Moskovitz. “Every religion, any person of faith, can celebrate and see that partnership,” he says.

Because this densely packed period of holy days are nearing an end, and months remain before the next holiday, Chanukah, the end of Sukkot ushers in the one-day holiday of Shemini Atzeret, the Hebrew name of which evokes a desire to linger, to extend a little the holy time. This is essentially just the eighth day of what would otherwise be a seven-day holiday, but it is, Moskovitz says, “a little less festive and little more filled with awe and reverence.”

On Shemini Atzeret, Jews start praying for rain, a supplication that, according to Moskovitz, seems more effective in Vancouver than in SoCal.

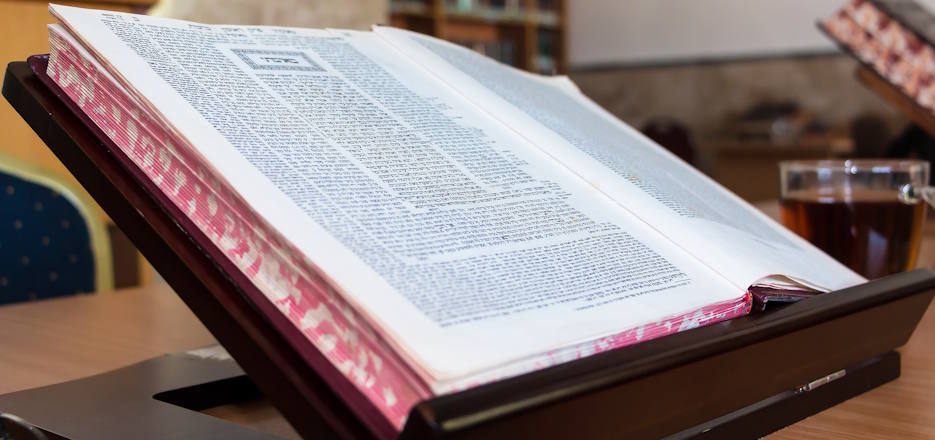

But wait. There’s more. The holidays are still not over. As the sun (such as it may be in Vancouver) sets on Shemini Atzeret, it ushers in Simchat Torah. This holiday marks both the completion and the beginning of the annual reading of the Torah. In Jewish tradition, the Bible is divided into 54 portions that are deliberated upon weekly. You may think there are 52 weeks in a year, but the Jewish calendar is “lunisolar” — based on both the sun and the moon — and since I was never good at either math or astronomy, I’ll just leave this fact here.

Regardless, the annual cycle of Torah-reading ends and begins Thursday night with the final words of Deuteronomy and first words of Genesis — an annual full circle that Jewish people worldwide will reprise for the several thousandth time.

“Simchat Torah is very symbolic of the cycle of reading and the continuity of this story,” the rabbi says. “The Bible is something that doesn’t change from year to year, but we change when we read it. We are different from one year to the next. We reflect on that difference as we read the text. We’re in a different place. We hear the story differently, even though the story hasn’t changed, so it becomes a wonderful barometer — how am I different from one year to the next when I read the story?”

While Sukkot emphasizes temporariness, Simchat Torah reminds Jews of something very permanent: the book that has bound them spiritually to one another and guided their values and actions across hundreds of generations.

.svg)